Wednesday 2 August 2017

A recent article entitled “All Lenders must be green lenders” by friend and EnergyPro collaborator in the US Sean Neil emphasised an important aspect of green and energy efficiency financing that often seems to be forgotten and which we have been writing about for a while. This is how do we ensure that all lending is green, or in the specific case of energy efficiency, how do we all ensure all financing achieves the optimum levels of energy efficiency. This text draws upon the EEFIG Underwriting Toolkit and work I carried out for KAPSARC on financing energy productivity.

Every working day loans, mortgages, leases and investments are made into new buildings, building refurbishments and modernisation as well as upgrade and replacement of industrial processes and production plants. In nearly all cases, energy efficiency is not the primary purpose of the investment being financed but the future levels of energy efficiency are effectively being decided and “locked in”, in some cases because of the long life of major assets for many decades. Although new buildings, refurbishments or new production plants generally achieve higher levels of efficiency than the units that they replace due to a) improved technologies and b) tighter regulations and codes of practice, many cost-effective opportunities to improve energy efficiency are missed. This occurs due to a number of reasons including; lack of knowledge on the part of project hosts, time pressure, the conservative nature of engineering design, and treating regulations as a target that have to be achieved rather than a minimum level of performance. Banks and financial institutions can play an active role in ensuring financed projects of all types achieve optimum levels of efficiency over and above business as usual by adjusting the lending/investing process to include queries about energy efficiency and the provision of assistance to identify viable projects. By doing this they can both reduce risks, by financing measures that improve customers’ cash flows, and potentially increase lending.

The EBRD has long been a pioneer in exploiting the opportunities provided by everyday, non-energy efficiency lending activities. As well as specialised efficiency projects the EBRD checks all industrial or commercial loan applications to assess potential for energy efficiency improvements. The bank then works with the client organisation to develop the priority projects and these are incorporated into the loan application. This process ensures that all commercially and financially viable improvements are incorporated, improves the client’s cash flow (which reduces the lending risk) and increases the capital deployed.

In commercial real estate funding for the acquisition or refinancing of a building an investor or lender will typically review the building’s financials, rent roll and history and require a Physical Needs Assessment (PNA) or comparable review. It can be a relatively simple matter to make energy efficiency assessments and ratings such as Energy Performance Certificates part of that PNA, and even to make performance standards part of a lender’s requirements. Some banks including ING and ABN Amro have implemented these kinds of programmes and are going further by providing tools to assist owners to identify energy efficiency measures.

ING Real Estate Finance (ING REF) set an ambition of reducing CO2 emissions from its Dutch portfolio by 15-20% with a target of energy cost savings of EUR 50 million per year. This entailed targeting 3,000 Dutch clients with 28,000 buildings. ING paid for the development of an app which was offered to all clients – the app provides an analysis of the clients energy use across their portfolio and identifies potential energy savings. If the potential energy savings exceed EUR 15,000 the client is offered a free site energy survey.

ING REF also provides advice to clients on what subsides are available (through a specialist third party) and ING REF offers 100% finance for energy efficiency improvements from ING Groenbank with a 0.5% discount on normal interest rates. Within the first two years, the app was used to scan 18,000 buildings with a total floor area of 10 million m2 (65% of ING REF’s portfolio). ING aims to roll out the app to other European countries.

The important thing here is that, as Sean says in his article, just by making small adjustments to existing processes for lending and investing, banks and investors could have a significant effect on future levels of energy efficiency, as well as identifying additional opportunities to lend and to reduce risks. Banks and investors need to ensure all projects they back, in whatever sector they are, real estate, industry, infrastructure, transport or energy supply, incorporate all cost-effective energy efficiency measures. If they don’t they are aiding and abetting developers and operators to lock in unnecessarily high levels of energy waste for the foreseeable future, sometimes even for decades.

Thursday 22 June 2017

The 22nd June sees the launch of the EEFIG Underwriting Toolkit – a major new publication aimed at assisting financial institutions build capacity in financing energy efficiency, particularly in regard to understanding and appraising the value and risk of energy efficiency projects. As its primary author, assisted by a great Consortium and input from many EEFIG members and others, it will be good to get the Toolkit into the market place after a year of work on it. Although primarily aimed at financial institutions looking to deploy capital into energy efficiency it should also be of use to project developers who can use it to develop projects more in line with the needs of financiers, and CFOs reviewing possible corporate energy efficiency investments who often face the same issues as external providers of capital.

With growing interest from financial institutions in financing energy efficiency projects, and increased recognition that investment and financing of energy efficiency has to grow by a factor of five by 2050 for us to have any chance of meeting our climate goals, it is time to address the elephant in the room on energy efficiency – performance risk. Recent articles in the UK press have highlighted the inadequacies of energy modelling, the performance gap between what a project is supposed to save and what it actually saves. Similarly in the US there has been disquiet about a number of PACE funded projects not performing.

The energy efficiency industry needs to come clean about performance risk and banks and investors contemplating scaling up capital deployment into efficiency need to understand the issue. This does not mean don’t invest in efficiency, or that it is high risk, it just means we need to really understand and where possible mitigate the risks.

So far most financial institutions have studiously ignored performance risk for the apparently rational reason that they are not taking it, or at least they think they are not taking it. Most energy efficiency financing at the moment is straight forward consumer or commercial lending, just and just like any other loan the borrower is on the hook for the payments come what may. The next largest area of efficiency financing is funding investments made under an Energy Performance Contract (EPC) where an Energy Service Company (ESCO) provides a guarantee that the predicted level of savings will be achieved and if they are not, pays the difference. So assuming the ESCO is experienced and credit worthy all is well for the bank, the project fails to deliver, the ESCO pays the client and the client pays back the bank.

However, things are really not that simple and even when financial institutions are not explicitly and contractually taking the performance risk they should be concerned about it for six good reasons:

- depending on jurisdiction consumer credit law it may make a lender responsible for equipment performance over its lifetime.

- under-performance can lead to customer dis-satisfaction which leads to disputes which put repayment at risk. They also consume time and energy on both sides and create a negative customer experience which these days can be quickly communicated and can cause reputational damage.

- some financial institutions count the improved cash flow resulting from the projected energy savings in their credit risk assessment. Even though they do not contractually take credit risk this means that they are implicitly taking performance risk, if the savings are not delivered the customer’s credit risk is higher than the assessed number.

- failures of project performance at scale in residential financed projects may lead to reputational loss, even a mis-selling scandal. In the US and UK there has been negative press about the performance of energy efficiency retrofits. Imagine if a bank financed millions of retrofits on the promise of savings being greater than repayments and they were not delivered, the reputational risks and the cost to rectify would be huge.

- a better understanding of performance risk will allow development of new products which take some performance risk for higher returns. This has started to happen in wind power for instance where lenders who previously would take no performance risk are now taking some for higher returns. Done right energy efficiency can be highly profitable and secure so there is an opportunity for a funder who really understands the risks.

- re-financing markets, specifically the green bond market, will require assurance that underlying projects are performing and having a genuine environmental impact. The green bond market is imposing more stringent standards on what qualifies as green. In order to attract the most investors at the best rates it is important to be able to prove that the underlying projects are actually performing as they were supposed to.

These six reasons mean that financial institutions active in, or contemplating entering the energy efficiency market really do need to understand and manage performance risk.

The Investor Confidence Project (ICP) is an international project to reduce performance risks and due diligence cost through the standardisation of energy efficiency project development. Under the ICP’s Investor Ready Energy Efficiency™ system, accredited project developers, who have to be highly qualified and experienced, develop projects following the ICP’s Protocols which are then independently reviewed by an ICP Quality Assurance professional. Projects that receive the Investor Ready Energy Efficiency™ certification have followed international, transparent best practice and therefore will have lower performance risk and financial institutions can spend less on due diligence – lenders and investors, as well as CFOs, can have more confidence in them. They also have on-going Operations & Maintenance and Measurement & Verification plans both of which help to maintain savings through the life of the project. Standardisation through the ICP will also enable aggregation which is necessary in order to utilise the debt capital markets.

ICP has Protocols available to use in the buildings sector, both tertiary buildings and apartment blocks in the US and Europe. Protocols for industrial efficiency projects, street lighting and district energy are under development in Europe with the support of the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme. Project Developers can get training and become accredited – helping to give customers more confidence in their projects.

Financial institutions looking to deploy capital into energy efficiency should engage with the Investor Confidence Project and require its adoption from their project developers and project hosts.

More details on the ICP: europe.eeperformance.org

The ICPEU and I3CP projects have received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 649836 and 754056. The sole responsibility for the content of this document lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Union. Neither the EASME nor the European Commission are responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Friday 19 May 2017

On 9th May I presented at the Flame Conference, Europe’s leading natural gas and LNG conference. This was a different audience for me as I don’t often present to the massed ranks of the energy supply industry. As I said during my introduction, my good news is usually their bad news. Here is a version of my presentation.

We are at the beginning of the perfect storm for energy efficiency with six major drivers all coming together. The drivers are:

- Policy

- Economics

- Finance

- Technology

- Business models

- Market infrastructure

My argument is that these drivers coming together will significantly accelerate the uptake of the energy efficiency potential and seriously dent future energy demand.

In Europe the EC released its winter package late last year which was entitled “Clean Energy for all Europeans”. Amongst its thousands of pages there were some significant proposals for energy efficiency including adopting a 30% binding energy efficiency target for 2030, a revised Energy Efficiency Directive, and a revised Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings. We already have policies on Near Zero Energy buildings, Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards, and mandated energy audits for large organisations every four years. On top of these policies we have significant public funding going into energy efficiency as Project Development Assistance, loans and guarantees. Outside Europe, despite the best efforts of the current administration, many cities and states in the US are ramping up their energy efficiency programmes as a way of reducing environmental impacts and creating employment.

On economics, those of us who have been long-term advocates of energy efficiency have always argued that improving energy efficiency is the cheapest, (as well as quickest and cleanest) way of meeting demand for energy services. Now we have the evidence on this. The Derisking Energy Efficiency Platform (DEEP), created by the Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group Derisking project, has data on more than 7,500 projects across industry and buildings. The mean cost of energy efficiency for buildings is 2.5 euro cent per kWh while for industry it is 1.2 euro cent per kWh. On top of the financial benefits from energy cost savings, it is increasingly recognised that energy efficiency brings with it many non-energy benefits including amongst others; improved health and well-being, increased productivity, and increased asset value. These non-energy benefits can be much more valuable and much more strategic to decision makers than simple energy cost savings, and therefore projects sold in this way are more likely to proceed. Energy efficiency projects should and are increasingly sold on these strategic non-energy benefits.

Finance is the next driver of change. For many years energy efficiency professionals said “there is no money for efficiency”. This is no longer true. There is a wall of capital looking to invest in energy efficiency because it is low risk and offers the most impactful way to influence emissions and climate change. Groups like the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change, which has 130 members with €18 trillion in assets, are pushing to increase the deployment of capital into energy efficiency. More than 140 banks have signed commitments to increase their deployments into efficiency. Finally the massive scale of the opportunity, perhaps the biggest money making opportunity on the planet, has been recognised. There is more money available than there are well developed projects. The issues now are all about practical ways to scale up the development and funding of energy efficiency investments.

Energy efficiency technology is moving rapidly and getting cheaper, and it is not all about LED lighting. New smart control technologies, artificial intelligence and retrofit prefabrication technologies are all getting cheaper. Innovations like Energiesprong offer rapid retrofits which can greatly improve living conditions, speed up retrofits to a week or less, and result in financed solutions that end up in a net zero energy house – something that will be deeply attractive to many consumers, particularly in markets like the UK where energy companies are deeply unpopular. The number of efficiency start-ups has increased and at the other end of the scale large companies are adapting and developing new technologies.

Along with technology and finance another important driver is business models. When people start talking about energy efficiency it does not take long for the conversation to shift to Energy Performance Contracts or EPCs. EPCs have been around a long time but remain a small market, the reason why they remain small is they don’t work in most sectors. They work in the US public sector and to a limited degree the EU public sector, but they don’t work in commercial real estate or in industry. New contract and business models are emerging such as Efficiency Service Agreements and Managed Energy Efficiency Agreements. In California and other US states there is real innovation in which energy efficiency is actually being metered just like any other energy supply. This allows several things; for the first time we can actually pay for performance rather than just pay for stuff like insulation and new boilers and hope it works, secondly efficiency can become a metered commodity and a reliable energy source like any others – something it has never been before.

On top of all these drivers we have a number of what I call market infrastructure developments. Chief amongst these is the Investor Confidence Project (ICP) which addresses one of the major barriers to scaling up investment into energy efficiency. This lack of standardisation increases performance risk, increase due diligence costs, prevents aggregation of multiple small projects and prevents banks and investors building teams around standard processes. The ICP through its Investor Ready Energy Efficiency™ provides a way of standardising through best practice, transparency and independent quality assurance.

So how far can we go in decoupling energy growth and economic growth? When I first became a student of energy in the late 1970s it was accepted that energy use and GDP were firmly coupled. All forecasts of demand were based on that idea. Then we moved to “relative decoupling” in which energy use grew less rapidly than economic output. After that came “absolute decoupling” in which energy use declines while economic output continues to grow. Since 2007/08 we seem to have entered absolute decoupling in Europe and the US.

We need to learn a lesson from history when thinking about future energy demand. In the 1970s two significant low energy scenarios were published. In 1976 Amory Lovins published “Energy strategy: the road not taken” in which he described “soft energy paths” and in 1979 Gerald Leach et.al. published “A low energy strategy for the UK”. Both of these were considered wildly optimistic at the time and widely panned by analysts, the energy industry and government agencies. History shows that they turned out to be more accurate than any official government or energy industry scenario. As I said in the title of a blog a while back; “Surprise, you are living in a low energy future”. What is more, we achieved that low energy future without really trying, except perhaps for a ten year period starting in the mid-to late 1970s.

So to answer an expanded version of the question in the title, “How much will technology / policy / economics / finance / business models and emerging market infrastructure reduce energy demand?”, a lot more than you think!

Friday 12 May 2017

On 2nd May I was fortunate enough to present at the G20 Energy Efficiency Forum and take part in a panel discussion. The G20 energy efficiency work has not got much attention but there are some good things happening and at the event the group, with 15 participating countries chaired by France and Mexico, launched its G20 Energy Efficiency Toolkit.

The toolkit offers a perspective on scaling up energy efficiency investments by defining and separating “core” EE investments – those stand-alone projects where energy savings are the main driver – and “integral” investments where overall asset performance is the lead driver but energy efficiency is delivered as one of multiple benefits over and above the main driver.

The global investment in energy efficiency has been identified by the IEA as $221bn with the US, EU and China representing 70% of the total. Within the EU 80% of the total investments were in buildings, with over 90% in Germany, UK and France. The toolkit reports that the largest “core” energy efficiency investment is in the market for Energy Performance Contracts which totalled $24 billion. I assume this means third party investment as internal balance sheet financed projects are surely much higher.

The G20 EE Toolkit offers advice to different groups including policy makers, private sector banks, institutional investors and the insurance sector. It also gives case studies from various countries including Mexico, France, China, Australia and others.

There are parallels with my energy productivity work for KAPSARC. In that I distinguished between “energy efficiency” investments and “normal investments”, a definition which parallels the G20’s “core” and “integral”. Energy efficiency investments are those where the main purpose is energy saving. This includes much of what we usually think of as energy efficiency, retrofitting buildings or production lines for example. While these are important at any one time hundreds of investment decisions are being taken on all kinds of infrastructure that will affect our energy consumption and emissions for the next twenty to fifty years or even beyond. Most of these are not “energy efficiency investments” but “normal” investments where the main purpose is not energy efficiency.

Pure energy efficiency investments can be ramped up by specialised funds or facilities and public-private partnerships with public finance providing development capital and guarantees. Any programme needs to:

- Provide finance

- Build pipelines of projects

- Build capacity in end-users, energy efficiency industry and finance industry

- Standardize development process, documentation, contracts and measurement

Encouraging the growth of the ESCO-EPC market also helps drive pure energy efficiency investments. This can be done through models like ESCO-EPC facilitation (e.g. Berlin, RE:FIT) and Super-ESCOs (e.g. Etihad).

It is also important to build market infrastructure through:

- Standardization of process (e.g. Investor Confidence Project)

- Standardization of contracts (e.g. standard EPCs)

- Standardization of Measurement & Verification

- Build evidence bases of project performance

- Build capacity within financial sector.

It is also important to continue to build demand through strong Minimum Energy Performance Standards and building capacity in energy management through standards e.g. ISO 50001

As well as ramping up pure energy efficiency or core investments we need to ensure the efficiency opportunities presented by normal investments are not being missed. Even if you design a building to code and that makes it low energy compared to existing buildings it is not really doing anything to improve the situation – I would not count it as an energy efficiency investment. It is a normal investment and a missed opportunity to include cost-effective energy efficiency measures. Every day, in design and investment decisions around the world, the economic potential to improve energy efficiency beyond business as usual is being missed. We need to change that through better regulation, capacity building amongst investors, specifiers and designers and implementing better design processes such as integrated design. Banks and investors can help this process by building in checks and questions during their investment decision making. These processes should force borrowers to review their specifications and designs. EBRD has been doing this for a long time. By doing this the banks can reduce customer risks by reducing their energy bills and increase the deployment of capital into cost-effective opportunities.

To scale up energy efficiency we need to take actions to increase the rate energy efficiency investments, and actions to increase the uptake of cost-effective efficiency opportunities within normal investments.

Monday 24 April 2017

The marches for science in many cities around the world this weekend were good to see. We often seem to be entering a world of anti-science, especially amongst the religious right in the US and the current administration. Groups like the anti-vaccination brigade and those who want to teach creation alongside evolution are bad signs of the growing power of anti-science. At the same time we are increasingly dependent on technology, much of which flows from a deep scientific understanding of the universe and how it works, at least in the little backwater that we inhabit. It is weird that the anti-science people still want benefits from science including clean water, cheaper and healthier food, medical treatment (apart from the ones they disagree with), electricity, the internet and mobile phones.

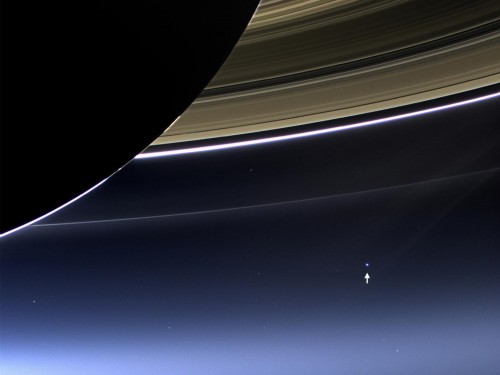

The great physicist Richard Feynman wrote an essay called “The Value of Science”. He talks about three values. Firstly the obvious one is the technology that flows from science. Technology is not always driven by science but the two things are increasingly inter-dependent. Science has allowed us to develop medicines that have eliminated diseases like polio and smallpox, it helped developed anaesthesia, it enables us to understand and harness electricity, it allowed us to develop micro-processors etc. etc. The list goes on and on. Feynman’s second value is the inspiration and enjoyment that comes from exploring the universe. Even if we personally cannot directly take part or fully comprehend much of the science it is inspiring to read and think about. Who cannot be at least a little inspired by scientists being able to decode DNA, or listening to the sound of radio signals received from pulsars by Jodrell Bank, or this picture of earth taken by the Cassini probe around Saturn? (The arrow mark earth).

The third value that Feynman identified is that science always deals with ignorance, doubt and uncertainty. He said:

“Now, we scientists… take it for granted that it is perfectly consistent to be unsure, that it is possible to live and not know. But I don’t know whether everyone realizes this is true. Our freedom to doubt was born out of a struggle against authority in the early days of science. It was a very deep and strong struggle: permitting us to question – to doubt – to not be sure. I think that it is important that we do not forget this struggle and thus perhaps lose what we have gained. Herein lies a responsibility to society.”

This is subtle but important. It is about our freedom to doubt authority. Scientists like Galileo challenged authority and science continues to do that to this day. The element of doubt Feynman refers to is so vital because the really dangerous people in the world are the anti-science people with no doubts.

Science is amazing. It is also part of what makes us human. Only a science based approach can make everyone wealthy and healthy and clean up the environment, which is what we need to do as quickly as possible. We should be massively increasing spending on science and science education not cutting it.

Sign of the day.

Dr Steven Fawkes

Welcome to my blog on energy efficiency and energy efficiency financing. The first question people ask is why my blog is called 'only eleven percent' - the answer is here. I look forward to engaging with you!

Tag cloud

Black & Veatch Building technologies Caludie Haignere China Climate co-benefits David Cameron E.On EDF EDF Pulse awards Emissions Energy Energy Bill Energy Efficiency Energy Efficiency Mission energy security Environment Europe FERC Finance Fusion Government Henri Proglio innovation Innovation Gateway investment in energy Investor Confidence Project Investors Jevons paradox M&V Management net zero new technology NorthWestern Energy Stakeholders Nuclear Prime Minister RBS renewables Research survey Technology uk energy policy US USA Wind farmsMy latest entries

- ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning’

- You ain’t seen nothing yet

- Are energy engineers fighting the last war?

- Book review: ‘Stellar’ by James Arbib and Tony Seba

- Oh no – not the barriers again

- Don’t assume ignorance, sloth, bias or stupidity

- Collaborations start with conversations