Tuesday 5 March 2019

I must admit I used to be a sceptic of the call to “electrify everything” but then that was back in the days when the carbon intensity of the UK electricity system was c.500 gCO2/kWh whereas now that intensity is down to c.250 gCO2/kWh. I also have to admit that I have been a sceptic on heat pumps and guilty of falling foul of one of the ‘human’ barriers to better energy management I identified back in my PhD in the early 1980s, i.e. a bias against a technology resulting from out of date experience, in this case the view that heat pumps were over-hyped and under-performing.

One of the problems with a long career in one field is that there are cycles of fashion and interest that seem to repeat, albeit with differences. Back in the early 1980s there was a push for industrial heat pumps. As is often seen in non-technical, or even semi-technical explanations of heat pumps it was said that “heat pumps are like refrigerators in reverse” (which we all know is wrong anyway as they are “running in the same direction” as refrigerators). One esteemed and highly technical expert at the time, who in fact wrote the book on industrial heat pumps which I still have on my shelves somewhere, said; “comparing heat pumps to a refrigerator is like comparing a Ferrari to a Mini. They both have four wheels and an engine but there is a huge difference in their complexity, their maintainability and their running costs”. That comment clouded my views on the enthusiasm to use heat pumps as an answer to decarbonising heat. Also, as with any technology there is no question that there were many bad installations, as always happen when there is a bubble and consumer facing hype gets ahead of installer capabilities.

My scepticism was made worse by stories like the one I reported in a blog on 28 March 2014 when the front page of the Independent on Sunday reported: “Exclusive: Renewable energy from rivers and lakes could replace gas in homes“ and the article started by saying “millions of homes across the UK could be heated using a carbon-free technology that draws energy from rivers and lakes in a revolutionary system that could reduce household bills by 20 per cent”. That piece of pure hype, which was wrong in so many ways, was aided and abetted by the then Secretary of State Ed Davey who really should have known better.

However, things change and when they do it is time to change your mind. The quote; “when the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do sir?’ is attributed to John Maynard Keynes although as with many other famous quotes apparently there is no proof he ever said it. It is clear that heat pump technology, particularly for space heating, has moved on. An article on LinkedIn by Paul Kenny of Tipperary Energy Agency, “How did the beast from the east affect heat pump performance” was very interesting as it recorded real-world performance of 16 residential heat pump installations during extreme cold weather in March 2018.

As well as advances in heat pumps the other thing that got me thinking more about electrification was some surprising data about the effects of gas cooking on indoor quality, particularly the effect on CO, CO2, NO2 and VOCs. Having grown up cooking with natural gas most of us have ignored the effects, thinking instead, if we did at all, that indoor air quality problems resulting from cooking were confined to developing countries where people cook on wood fires or kerosene stoves in poorly ventilated spaces. It turns out that we have an indoor air quality problem from cooking as well – particularly in badly ventilated kitchens. Lloyd Alter produced a good summary here. The answer is to go electric. Induction hobs are the way to go for fine control of cooking as well as improving indoor air quality.

It is clear that we are moving to a more electrified future, in heat and ultimately transport. For new build the only way to go is to mandate Passive House standard and therefore cut heat loads so much that direct electric heating (possibly with storage to allow households to take advantage of PV generated power and to interact with the electricity market) is viable. For retrofit situations where taking the building to Passive House standard is not possible technically or economically there is definitely no one silver bullet and fully electrifying the entire current heating load is clearly not going to be possible because of its impact on the electricity supply system, as Michael Liebreich pointed out, “in a normal year, the UK’s winter heating load – which is practically zero in summer months – reaches peaks six times as high as the country’s electricity load, and it can cycle up and down by a factor of three in just a few days.” Having said that heat pumps will have a growing role to play, either for individual homes or perhaps group heating schemes with thermal stores that also interact with the electricity flexibility market. Other emerging technologies such as “heat batteries” or thermal stores will also have a role to play in electrifying heat alongside heat pumps.

For more real world examples of completely electrifying homes in the harsh climate of the US mid-West check out the excellent work of Nate The House Whisperer

After finishing this blog I discovered the DryFiciency project, an EU Horizon 2020 funded project to develop high temperature industrial heat pumps with the aim of reducing specific energy for drying/dehydration/evaporation processes by 60-80%. Industrial heat pumps may yet have their day.

Tuesday 19 February 2019

The Paris Agreement of December 2015 signalled an international intention to mitigate climate change and attempt to contain the global temperature rise. To have any chance of achieving the targets we need to step up investment into clean energy and energy efficiency. The World Economic Forum stated that the Paris Agreement was a $23 trillion investment opportunity. Carbon Brief estimated that to achieve a 1.5°C investment into clean energy would need to be 50% higher. The IEA says that to achieve its Efficient World Scenario would require investment in energy efficiency, currently about $270 billion a year, to double between 2017 and 2025 and then double again between 2025 to 2040. The European Commission estimate that to achieve its energy and climate goals requires an additional investment of €170 billion per annum.

So how is Europe approaching the need to steer more investment into clean energy and energy efficiency, as well as wider sustainability objectives? In 2016 the EC convened the High Level Expert Group (HLEG) on Sustainable Finance to provide advice on how to ‘steer the flow of capital towards sustainable investment; identify steps that financial institutions and supervisors should take to protect the financial system from sustainability risks; and deploy those policies on a pan-European scale’. The HLEG met from December 2016 to December 2017 and its report made the following recommendations:

- Introduce a common sustainable finance taxonomy to ensure market consistency and clarity, starting with climate change.

- Clarify investor duties to extend time horizons and bring greater focus on ESG factors.

- Upgrade Europe’s disclosure rules to make climate change risks and opportunities fully transparent.

- Empower and connect Europe’s citizens with sustainable finance issues.

- Develop official European sustainable finance standards, starting with one on green bonds.

- Establish a ‘Sustainable Infrastructure Europe’ facility to expand the size and quality of the EU pipeline of sustainable assets.

- Reform governance and leadership of companies to build sustainable finance competencies.

- Enlarge the role and capabilities of the European Supervisory Authorities to promote sustainable finance as part of their mandates.

The report was followed quickly by the Commission publishing an Action Plan on Sustainable Finance in March 2018. This included:

- Establishing a common language for sustainable finance, i.e. a unified EU classification system – or taxonomy – to define what is sustainable and identify areas where sustainable investment can make the biggest impact.

- Creating EU labels for green financial products on the basis of this EU classification system.

- Clarifying the duty of asset managers and institutional investors to take sustainability into account in the investment process and enhance disclosure requirements.

- Requiring insurance and investment firms to advise clients on the basis of their preferences on sustainability.

- Incorporating sustainability in prudential requirements.

- Enhancing transparency in corporate reporting.

The Commission also published three legislative proposals covering the taxonomy, disclosure and duties and benchmarks. Then in July 2018 the Commission convened the Technical Expert Group (TEG) to assist the Commission in developing:

- an EU classification system – the taxonomy – to determine whether an economic activity is environmentally sustainable

- an EU Green Bond Standard

- benchmarks for low-carbon investment strategies

- guidance to improve corporate disclosure of climate-related information.

The TEG will report on its taxonomy proposals by June 2019. On energy efficiency, the latest iteration of the Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group (EEFIG), supported by the EC and UN Environment, will feed directly into the work of the TEG on the taxonomy.

The Commission is moving quickly to put in place a framework that will help steer investment into sustainable activities. This first phase is focused on climate change mitigation and adaptation but future phases will also start to examine other aspects of sustainability including; healthy natural habitats, water resource conservation and management, waste minimisation, pollution prevention and control, agricultural and fisheries productivity, access to food, access to basic infrastructure and access to essential services.

To achieve improved levels of sustainability we need to increase investment flowing into sustainable projects, assets and sectors. The investment needs can only be met from the private sector. The EC is moving quickly and Europe is leading the world in building the enablers that will direct more capital into sustainable finance. Ultimately however success will be measured by changes of direction and increases in the flow of capital into more sustainable activities.

Wednesday 30 January 2019

The end of January (30th) brings another significant birthday, (one that I have trouble believing), and those events are an excuse for some retrospective thinking as well as consideration of the future. I thought I would briefly review “my life in energy”, trying to explain some of the influences on me, set against the unfolding energy transition, so please indulge me.

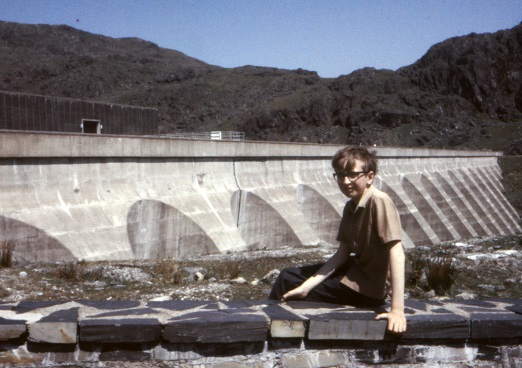

In the 1960s I really liked visiting North Wales. Snowdonia, the castles and the Ffestiniog Railway all combine to make North Wales a special place. One year we visited the Ffestiniog pumped storage hydro scheme. The scale of the engineering and the vision to dig tunnels and caverns out of the mountainside, as well as the storage aspect was fascinating. It is an amazing piece of engineering and epitomises the central planning of the nationalised electricity industry of that time. It also made the energy industry exciting.

c.1967 visiting the Ffestiniog Power Station

The 1970s were dominated by the two oil crises of 1973/74 and 1979. Although of course the 1973/74 oil crisis was caused by the OPEC embargo in response to the Arab-Israeli war rather than any physical shortage of oil, it did mark a seismic shift of power from consumer nations to the producers and a change in the way that we viewed energy. In the UK it rolled into the three day week caused by the coal miners’ industrial action and regular power cuts which really brought home what life without electricity would be like – even in the relatively simple world of the 1970s. As well as missing favourite TV shows, which of course were not at that time available at any other time or on any other media (hard to imagine now), doing homework by candle light made me realise what it must have been like for previous generations or people in countries without access to electricity. This period also saw the environmental movement gaining momentum. The three day week definitely influenced my choice of degree course, an inter-disciplinary degree called Science of Resources with a focus on energy, once I had convinced myself that the aeronautical industry was in a terminal decline and that being an astronaut was fairly unlikely. In the summer of 1979 I was in the US when people lined up for gas and gas hit the heady heights of 86 cents a gallon, 25% up from the year before.

In the 1980s I started work doing energy audits and then a PhD looking at the potential for energy efficiency in British industry with a focus on sectors that my PhD supervisor christened the boozy industries – brewing, distilling, malting and dairies. I spent much time visiting sites including most of the breweries in the country – a tough gig for a PhD student. The UK brewing industry led the world in developing an annual energy benchmarking exercise, one that I think is still going, probably represents the longest time series data on the energy consumption of an industrial sector anywhere in the world.

The 1990s started with the world changing collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin wall, as well as the privatisation of the electricity and gas industries in the UK. The two combined to change my life, privatisation led to energy prices falling sharply and everyone taking their eye off the ball of efficiency by the mid-1990s but the fall of the Soviet empire led to opportunities in Central & Eastern Europe. I spent a fascinating four years working in Romania at a time when the rate of change was visible. Amongst other things I designed EU assistance programmes, advised the Ministry of Industries Agency for Energy Conservation, co-founded an ESCO which is still going, and sponsored two orphans. The early 1990s also saw the introduction of the Non-Fossil Fuel Obligation and the emergence of the then tiny wind industry. Delabole, with its ten 400kW turbines, opened in November 1991.

The 2000s were my introduction to energy services, firstly through Enron (which actually was a great place to work) and then RWE. My brewing industry PhD proved useful when we gained Guinness as a client, first at Park Royal with Enron & then Park Royal, Dublin and Dundalk breweries with RWE. We took Park Royal from being the least efficient brewery to the most efficient but it sadly had to close due to restructuring within Diageo and concentration of production in Dublin. In that period I learnt to like drinking Guinness, a skill I have now lost. The Guinness and Sainsburys deals that we developed with Enron and then delivered through RWE were really ground breaking and some of the things we worked on, like demand response on commercial refrigerators, only came to pass much later. We also applied integrated design and right sizing principles. In the late 2000s my focus switched to finance – first doing equity research in new energy and clean tech and then corporate finance. It felt like a big change of direction but given that Enron operated more like an investment bank I now see the decade more as a gradual shift towards finance. In 2012 I founded EnergyPro with the purpose of bringing more capital to energy and resource efficiency, something we are doing through advisory work, asset management and fund raising. Looking forward I see growth in energy services, sustainable infrastructure and the intersection of technology and infrastructure – infratech. More and more of our activity will be linked to the Sustainable Development Goals which form a clear set of targets for society, organisations and individuals.

It has been interesting to witness and fulfilling to participate in the energy transition and I look forward to continuing to do that. Energy transitions take a long time but it is worth taking a look back occasionally and see how much change there has been. We still have a long way to go but I am reminded of Arthur C. Clarke’s quote: “we tend to over-estimate what we can achieve in the short-term but under-estimate what we can achieve in the long-term”.

Monday 14 January 2019

Elegance: The quality of being pleasingly ingenious and simple; neatness. (Oxford Dictionary)

The economic and environmental advantages of energy efficiency are extremely well documented. As well as the value of avoided energy use we now recognise the economic and social value of multiple non-energy benefits as diverse as increased productivity, improved health and better learning outcomes. The case for low energy, high performance buildings, and for retro-fitting existing buildings to achieve high levels of performance is clear. Furthermore the combination of near zero energy design, local generation through solar PV and demand response technologies mean that we are moving into an age where buildings are becoming prosumers, both producers and consumers, of energy rather than simply consumers.

There is another little explored characteristic of energy efficiency and that is elegance. In all areas, not only buildings, we have the technology and the know-how to design systems that are highly energy efficient, even energy positive – but we don’t typically use them because we engineer systems using conservative thinking and standard techniques. These systems are clunky (defined as “solid, heavy and old fashioned”) in their use of materials and energy, much of which is simply wasted. Think about a conventional UK house, which even though today’s Building Regulations are much improved, is still typically heated by a gas boiler feeding radiators and leaks heat like a sieve. The ‘boiler’ takes in gas, sets fire to it, and heats water which is pumped around panel radiators which heat up the rooms until a thermostat, often positioned badly and many of which are still based on the technology of bi-metallic strips (invented in the 1830s), and most of which are certainly not “smart” by any stretch of the imagination, detects that the temperature has been reached and sends a signal to turn off the boiler. The “bang bang” nature of the control leads to imprecise control with overshoots and lags, leading to more wastage. The construction of the house allows heat to leak away through the structure and via air infiltration, resulting in the consumer having to pay excessive energy bills and creating unnecessary carbon dioxide emissions and local heating effects.

Considering the wider system, the house takes in gas from a gas distribution system which is fed by the transmission system. Gas is fed into the system having been extracted from under the ground and treated to remove non-methane hydrocarbons and impurities such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulphide. Each of these steps involve massive equipment and capital expenditure, use significant amounts of energy and produce by-products and waste streams. They can be amazing pieces of chemical engineering but they are not elegant.

Now contrast that clunky system with a house designed to Passive House standards. It will have very high levels of insulation, higher performance windows and doors, a vapour barrier and a mechanical ventilation system with heat recovery. It will use 5-10% of the energy of a comparable house built to normal standards. The residents will feel more comfortable thanks to the internal surfaces having a higher temperature and the absence of draughts. They will also live in cleaner, healthier air. Imported energy will be electricity from a decarbonizing grid, (admittedly with all of its own inherent complexities and in-elegance), or in the case of a zero energy building from solar PVs linked to battery systems.

Simply put, as well as a number of other advantages such as low running costs, healthier environment and greater resilience, a Passive House building has elegance; the quality of being pleasingly ingenious and simple; neatness.

It is not only in building design that we see these characteristics. Many industrial systems use components that are based on primitive engineering such as process water bath heaters, the design of which dates back many decades. Newer, elegant systems can reduce energy usage by 50% or more. Internal combustion engine powered cars are miracles of industrial engineering but with their thousands of components and maintenance requirements, albeit much reduced over the years, they appear positively clunky compared to an electric vehicle.

As well as elegance in the final output there is something elegant about a design process itself that seeks high performance with the minimum amount of energy and resources. It requires real thought and effort compared to producing a standard “off the shelf” design. It requires thinking about what can be taken away, in the words of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry the French pilot and author; “a designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” In a similar vein Matthew E. May, a consultant on lean development has said: “The goal of elegance is to maximize effect with minimum means” and that “Elegance is a stop doing something strategy”. It is time we demanded elegance in design and stopped accepting conventional, clunky, energy guzzling buildings, industrial systems, vehicles and other stuff.

Have a more elegant, more efficient, more effective and healthy 2019.

Tuesday 20 November 2018

During my visit to Delhi to be a judge for the INSPIRE 2018 event I was privileged to be asked to speak to EESL managers on international developments in energy efficiency. I say privileged because talking to EESL about energy efficiency is like taking coals to Newcastle (as we used to say when there was a UK coal industry), or selling sand to the Middle East or snow to the Eskimos. EESL’s programmes such as UJALA, smart meters and EVs are massive in their scale, inspirational in their ambition and vitally important for Indian and global development. The rest of the world has a lot to learn from them.

Here are some brief thoughts that emerged from my presentation.

Context

To achieve our energy and climate goals we need to greatly ramp up investment into energy efficiency. The recently published 2018 Energy Efficiency Market report highlighted that we need to double the current level of investment into energy efficiency (c.$260 bn) by 2025 and then double it again by 2040. Although this is ambitious when I look around the world I see a number of emerging trends that make me optimistic that energy efficiency can start to fulfil its huge economic and environmental potential. For forty years we have known the scale of that potential but also known that the uptake of cost-effective potential remains low.

Energy efficiency technology innovation

Energy efficiency technologies are being deployed across all sectors; buildings, industry, appliances, energy production, transport and information technology and new technologies are appearing. We don’t actually need new technology to achieve our ambitions, just increasing the rate of application of existing, well proven, cost-effective technology, however innovation is always happening and appears to be accelerating. The application of IT and big data in particular is an area that is rapidly evolving and has huge potential. The application of AI, as demonstrated by the use of Deep Mind in Google data centres that saved 40% on already efficient centres highlights the potential. Another end of the spectrum is the redesign of basic equipment such as process heaters such as those from ProHeat. Like much of our infrastructure the basic design of process heaters has not changed for decades (or even a century or more) and the technology was designed when energy usage or costs were not considered. Re-design of basic equipment like process heaters, using thermos-syphon heaters, can save 45% of energy use in very high energy using equipment.

Changing electricity markets

Electricity markets everywhere are changing rapidly with the deployment of renewables, decentralisation and the emergence of prosumers, as well as electrification of transport and heating. The emergence of the ‘duck curve’ is creating problems for network operators grappling with the need for greater quantities of, and faster responding flexibility. Distributed energy resources including localised solar, demand response, battery storage, and vehicle to grid solutions will all play large parts in future electricity markets. If energy efficiency is to exploit this change we need to rethink it and make it measurable, reliable and able to be contracted for. We also need to recognise that like other distributed energy resources energy efficiency will have different values at different times and in different locations – in highly constrained network areas and at constrained times energy efficiency will have more value. Technologies like OpenEE enable the measurement and valuation of efficiency as a distributed energy resource.

Changing customer requirements

Another change, or perhaps it is not a change at all, is that most consumers don’t really care about energy efficiency at all. They care about strategic issues like resilience, productivity, health and well being etc. We are only just recognising the importance and value of non-energy benefits which usually are more strategic and more interesting than cost savings. Non-energy benefits will become increasingly important in preparing better business cases, something that the energy efficiency industry has traditionally been bad at. Simply justifying efficiency on its payback from energy savings is not enough, we should emphasise the strategic non-energy benefits and sell energy cost savings almost as a side effect.

Growing interest from financial institutions

Over the last five to ten years financial institutions have become interested in energy efficiency and this has to be a good thing. Having said that efficiency presents many problems to institutional capital including lack of standardisation, lack of scale and lack of capacity within financial institutions. These factors are now being addressed through projects like the Investor Confidence Project and the EEFIG Underwriting Toolkit.

Growing recognition that energy efficiency projects do have risks

It was always said that energy efficiency was very low, or even zero risk. There is no such thing as a zero risk project anywhere – if you can find one invest in it. We are finally recognising, and more importantly gathering data on, the real performance of projects which shows, not surprisingly, that some projects over-perform and some under-perform, but in a portfolio the performance is usually good. This recognition and data will enable new financing solutions and insurance products that utilise the portfolio effect and can make financing easier.

Increased activity in financing efficiency

We have many mechanisms for financing efficiency and they can be used for different situations and market places, but there is no silver bullet or need for new ‘innovative financing methods’ (often code for subsidy or grant in some form). What seems to be true, however, is that to get finance to flow at scale it is necessary to bring together four elements: finance – both risky development finance and low risk project finance; a way of building pipelines of projects; standardisation in project development, documentation and underwriting, and capacity building in the demand side, the supply side and the finance industry. This is what I call the jigsaw of energy efficiency financing. There are different ways of organising but all successful examples such as EESL, the Etihad Super ESCO and the Carbon & Energy Fund in the UK, bring these four elements together.

Conclusions

As all the trends described above continue to emerge and grow, the huge global energy efficiency resource in all sectors will become easier to exploit and investment levels will grow, resulting in energy use and cost reductions beyond the standard, official forecasts, as well as bringing the many valuable non-energy benefits.

Steve Fawkes, Managing Partner, EnergyPro, receiving thanks for being part of the INSPIRE 2018 judging panel from Shri R.K. Singh, Hon’ble Minister of Power, New & Renewable Energy, (I/C), Govt. of India.

Dr Steven Fawkes

Welcome to my blog on energy efficiency and energy efficiency financing. The first question people ask is why my blog is called 'only eleven percent' - the answer is here. I look forward to engaging with you!

Tag cloud

Black & Veatch Building technologies Caludie Haignere China Climate co-benefits David Cameron E.On EDF EDF Pulse awards Emissions Energy Energy Bill Energy Efficiency Energy Efficiency Mission energy security Environment Europe FERC Finance Fusion Government Henri Proglio innovation Innovation Gateway investment in energy Investor Confidence Project Investors Jevons paradox M&V Management net zero new technology NorthWestern Energy Stakeholders Nuclear Prime Minister RBS renewables Research survey Technology uk energy policy US USA Wind farmsMy latest entries

- ‘Here we go again’ – but this time we have a choice

- The corruption of purpose in business – and how to address it

- Gee, I wish we could have a white Christmas, just like the old days….

- A look back at the last forty years of the energy transition and a look forward to the next forty years

- Domains of Power

- Ethical AI: or ‘Open the Pod Bay Doors HAL’

- ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning’