Wednesday 25 January 2017

This is a version of the presentation I made at the EASME Energy Efficiency Finance Market Place held in Brussels 18th-19th January 2017.

Good morning, today I am going to talk about three important words for the energy efficiency finance market, standardisation, data and risk.

I am going to start off talking about the so-called low-hanging fruit of energy efficiency, one of the most frequently used and mis-used phrases in energy efficiency. As some of you know I have been spending some time in Saudi Arabia in the last year and there are some very significant things happening in energy efficiency down there. This picture shows some low-hanging dates – by the way if you have not had fresh Saudi Arabian dates you need to try them, they are delicious – but anyway, we need to ban the phrase low-hanging fruit.

This next slide shows that investing in energy efficiency is hard work, really hard work. This is the current situation. It is really hard to deploy capital into energy efficiency, deals take a long-time, deals fall apart after long development periods, and many funds have had trouble deploying capital – sometimes even having to return capital to investors because they cannot find viable deals.

Where we need to get to is summed up in the next slide. We need to move towards large-scale, automated processes for investment – just like we have in other financial markets.

I have talked many times before about the need for standardisation in energy efficiency. EEFIG said it was a major problem, Citi Bank have said it is a major problem, and other players like the IEA have agreed. In fact that need for standardisation was the genesis of the Investor Confidence Project. ICP standardises the development and documentation process for energy efficiency projects in buildings. I found another quote about standardisation that I like: “Standards are like DNA. They are the basic building blocks for all technology and economic standards.” All financial markets are based on standards. The industrial revolution was based on standardisation.

So what do we need to standardise? Firstly the development and documentation process for energy efficiency projects. This is what the Investor Confidence Project does. It now exists. It can be used in all countries in Europe and in the USA. Please use it. It works.

Secondly, we need to standardise the understanding of risks and value. This means counting all the sources of value created by energy efficiency projects and being very clear about all the risks. This is the subject of the Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group’s “Value and risk appraisal framework for energy efficiency finance and investments” which we are developing for EEFIG and which will be published in the summer.

Next we need to standardise contracts. A lot of work has been undertaken on this in the context of Energy Performance Contracts (EPCs). There are now several European standard contracts and guides for EPC. Of course, as I have said before, we need to develop other contract models that address the problems that EPCs don’t address. Standard contracts exist and can be used.

Finally we need to standardise performance data and reporting. We are now seeing a number of initiatives to do this including EEFIG’s DEEP. I encourage you to use DEEP and provide additional data for DEEP.

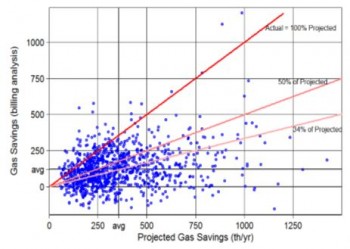

Let’s look at the risks of energy efficiency. When I started in this business many years ago everyone said energy efficiency has no or low risk. Even now people say this. Here is a recent quote I found which will remain anonymous: “The returns are tremendous, and there’s virtually no risk”. This simply is not true. Here is some data from some US projects which show that energy efficiency projects using standard technologies rarely achieve what they are projected to. If you were an investor in these projects, whether you are a householder or a bank, you would not be very happy.

The EEFIG “Value and risk appraisal framework for energy efficiency finance and investments” is a guide to assessing value and risk and aims to provide a common language for project developers and financiers. As well as the document there will be a web based version which will allow anyone to access summary information, more details as well as specific process related resources and references.

Now let’s look at data. Henry Ford launched the first mass-market car the Model T in 1908 and started to change the world. By 1919 car loans were developed and really opened up the market for cars. Therefore we have data on car loan performance for nearly a century. We have data on mortgages for even longer. However, there is still very little data on energy efficiency projects and how they perform. This is due to a number of reasons including:

- Metering and measurement is difficult

- Measurement and Verification relatively new and still not widely used

- Contract forms like EPC mask performance risk

- Performance data considered proprietary.

Data sources are now emerging, or at least the first versions of data sources. The first is DEEP which I mentioned before. There is also Building Button which has been launched by the Investor Confidence Project. The Building Button allows project developers developing projects using the ICP protocols to push a button and start collecting real performance data in a standardised way. There is also The Curve. However, right now even these innovations still have very little real performance data. Collecting and making performance data available is a new concept and of course collecting time series data needs time. An essential part of any future data platform is a common, open source language like BEDES in the USA. Without that we cannot compare like with like, or build data platforms which enable anyone to build apps that mine data for their own specific purposes. The ICP Building Button is based upon BEDES.

So let’s pull together standardisation, data and risk.

First of all different sources of finance take different risks. There is equity which takes equity risks and debt which takes debt risks, and all the shades in-between. PACE financing in the US for example, is based on property tax which is senior to mortgages and is therefore very low risk. People have to pay their PACE repayment on their property taxes or the local government takes over their house. Energy Performance Contracts transfer performance risk to an ESCO but what is the price of transferring that risk? Often too high I think.

We need to move towards a world in which the risks are sliced up and transferred to the parties most willing and able to take those risks. The role of insurance is important here and we are seeing some insurance companies step up to take performance risk, a trend that will expand. Emerging business models like Managed Energy Service Agreements or Metered Energy Efficiency Transactions address risk in different ways. Finally of course, the ultimate source of low-cost capital, the debt capital markets, requires a lot of standardisation and data.

So to sum up, right now we are still in a world in which investing in energy efficiency is a niche activity and is really, really hard work. To move to a world in which it is mainstream and easy we need to make it like every other financial market. To move to that future we need standardisation, acknowledgement and understanding of risks, and data ….. data, data and data.

Thank you.

Thanks to EASME for organising the Energy Efficiency Finance Market Place which was very successful with over 400 attendees which demonstrates the growth of interest in the market.

Friday 20 January 2017

I read that President Trump said that energy regulations are hampering economic growth and that his new administration will dismantle a whole range of regulations. This reflects an archaic way of thinking about economic growth – the old paradigm. My starting point is that we do need to seriously increase global economic growth to get us out of problems caused by poverty. This may be controversial but we only have a real chance of solving our many problems and achieving positive goals if we make everyone rich. The question is what kind of growth do we want or need? In the Trumpian view of the world it appears that all economic growth is good, even if it damages the environment, or health and safety, or exploits workers. Externalities such as pollution, health or wage fairness are not considered. This is the robber baron capitalism typical of 19th century America and which is still being practiced in many other places in the world. It has no consideration of consequences or of the quality of economic growth.

Considering the quality of economic growth led me back to one of my all time favorite books, “Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance” by Robert Pirsig. For those that haven’t read it, go and get a copy as soon as you finish reading this but be prepared for a difficult, though ultimately rewarding, read. By the way, it is not about motorcycle maintenance but is rather about a philosophical journey that explores the nature of human experience. Pirsig talks about quality or value and says that it cannot be defined because it empirically precedes any intellectual construction of it. It is that sense you get from the numerous sensory inputs that you have before you intellectualise it.

So what kind of economic growth do we want, and need? Economic growth that pollutes the environment, or is based on exploitation of workers, reduces the quality of our experience – sometimes in a sub-conscious way which contributes to a “dis-ease” – but always with an impact on our experience. It is most obvious in examples such as clean air. People want clean air – breathing clean air is a pleasant high quality experience, breathing polluted air in places like Beijing, or increasingly London, reduces the quality of our experience. This negative effect is over and above the clear economic benefits of having clean air such as reduced health care costs from the reduction in respiratory disease. At the micro-level our quality of experience is increased by certain buildings – you know the ones that make you feel good when you walk into them. Likewise there is that positive sense of well-being, a high quality experience, that comes from being in beautiful countryside.

So we need to have economic growth that improves our quality of experience. This means growth that reduces quality sapping factors such as air pollution, growth that does not rely on exploiting workers at home or abroad, growth that repairs and restores environmental damage, growth that reduces our fears about climate change, growth that builds beautiful buildings and cities, growth that creates beautiful and uplifting landscapes, growth that comes from radically improving energy and resource efficiency.

The Trumpian view of growth may appear to be in the ascendancy right now because of the high profile of the US Presidency, but at the micro level many, many businesses, large and small, as well as individuals, are committing to more sustainable business models and practices. In the medium term the trends are unstoppable because people naturally seek higher quality experience – it is hard wired into our DNA. We are witnessing a short-term reaction from the old guard which is typical of the collapse of a paradigm. The robber baron mentality will ultimately be confined to where it belongs – the history books.

Thursday 22 December 2016

It is that time of the year when journalists and bloggers – me included – struggle to come up with a Christmas or New Year themed piece. Having started an energy efficiency review of the year I decided instead to focus on one development that I believe will have big implications for energy efficiency and energy markets in 2017 and beyond – the Building Button.

2016 brought many changes in the energy scene with the oil price, fracking, the falling cost of renewables and new nuclear all making the headlines. In December the Investor Confidence Project unveiled its latest innovation, one that promises to change the way that energy efficiency is exploited and financed, the Building Button.

Essentially the Building Button allows project developers using the ICP’s Investor Ready Energy Efficiency™ project certification system to literally push a button at the end of the development process and have all the data transferred into a standard form based on the US Department of Energy’s BEDES “dictionary” of terms. This allows project data to be collected in a standardized way which will allow market participants including investors, lenders, insurers, building owners and developers to share, aggregate and analyze project level data. This is an important first for the energy efficiency industry which up to now has been characterized by a lack of real data – a lack that reduces project host and investor confidence, and inhibits the growth of demand for efficiency upgrades.

Building Button is built around three use cases: Technical Due Diligence, Financial Underwriting and Actuarial Data. It can be used across organizations or within an organization wanting to track project data including on-going project performance data. We see applications for aggregators, utilities and large portfolio owners wanting to standardize project development and data and ultimately measure the real performance of their energy efficiency investments.

The Building Button label sounds strange in Europe but it is derived from other “buttons” used in the US; the green button which allows consumers to download their energy consumption data, the orange button which standardizes data collection for the solar industry, and the blue button which signifies healthcare sites where patients can download their medical records.

Along with the standardization of project development and documentation brought about by the Investor Confidence Project – as well as the Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group’s guide to value and risk appraisal in energy efficiency investing, the launch of the Building Button puts in place the basic market infrastructure which is needed to build confidence and grow the energy efficiency project market. It also lays the foundations for pay for performance models which will really push the button on growing demand for energy efficiency, a subject I am sure I will return to in 2017.

To learn more about the Building Button join the ICP webinar on 9th January at 0900 PST.

To all my colleagues, collaborators and customers, readers of onlyelevenpercent.com and followers on Twitter and LinkedIn, have a very merry and peaceful Christmas and a healthy and prosperous 2017.

Tuesday 22 November 2016

I heard the Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond yesterday morning talking about the Autumn statement and the need to build resilience in the UK economy. At the same time there has been a lot talk about productivity since the change of government. The Chancellor himself said at the Conservative conference: “to deliver that strong, prosperous, economy……requires long-term, sustainable growth. And long-term sustainable growth requires us to raise our national productivity.”

Given these kinds of statements, and the energy situation we have, it is time to prioritise a policy and a target that would both improve resilience (to economic shocks) and improve productivity – specifically energy productivity, and put in place policies and programmes that drive energy productivity. In the old world energy was an input to the economy and the demand for energy was driven by growth in the economy. Now improving energy productivity itself has been shown to be a driver of economic growth.

Energy productivity is defined as GDP per unit of energy, how much value we create from every unit of energy. At the end of the day we all want increased GDP. I know it is an imperfect measure of welfare but making people richer is what drives improvement in the human condition, here in the U.K. and everywhere else. (Yes – I know that wealth also creates problems but we are not going to get out of those problems by becoming poorer – we will only get into other deeper problems). Given the energy issues that the UK is facing – including declining domestic energy production, increase reliance on imports, very tight electricity supply margin, environmental impacts that lead to health problems (a global impact through CO2 emissions and local impacts through air pollution), and poor energy efficiency in housing that leads to fuel poverty – adopting an energy productivity target and strategy should be a priority.

Energy productivity goes beyond the traditional perspective of energy efficiency and is more than a simple reframing of the energy efficiency agenda. Ultimately the trajectory of energy productivity in an economy is driven by three factors; the energy productivity of existing capital stock, the energy productivity of new capital stock, and the structure of the economy.

Increasing energy productivity of the existing stock, (which is normally the province of energy efficiency and energy management), all other things being held equal will increase the energy productivity of the economy. The methods to do this at the macro level are the subject of energy efficiency policy – which we know how to do and is well documented.

Increasing energy productivity of new stock entails ensuring that new stock, across all sectors, is as efficient as possible within the definition of economic. Although new stock, new buildings for example, will tend to be more efficient than old stock due to advances in technology and tightening regulations, many cost-effective energy efficiency opportunities are missed due to many factors. This lever of energy productivity can be effected by regulations that are normally considered part of energy efficiency policy e.g. building codes, but importantly, and largely neglected to date, it can also be changed by finance and investment policies – areas outside conventional energy efficiency policy. For example public infrastructure funds could have a policy of only investing in high energy productivity stock, (for instance top quartile performance) and working with project sponsors to identify cost-effective energy efficiency opportunities – as has been practiced by the EBRD for many years. Investing in new stock that has an energy productivity higher than the average (for the economy or the sector) will increase overall energy productivity. Other finance and investment policies that would drive improvements in energy productivity include requiring banks to assess the energy productivity of their loan portfolio, facilitating the growth of the green bond market for high energy productivity assets, and reducing capital reserve requirements for high energy productivity assets.

The third driver of energy productivity is diversification within the economy e.g. a move towards higher energy productivity activities. This is the province of economic development and industrial strategy policies. Energy productivity can be applied to all sectors of the economy and it is an integrating policy.

At a corporate level adopting an energy productivity target also drives activity in the three areas; retro-fit, refurbishment and new build – and helps to balance them within a coherent, and strategic policy. Strategic issues always get more attention than non-strategic things and are not subject to the same short payback criteria normally applied to retrofit. Energy management is usually only concerned with retrofit and is consigned to the boiler room rather than the board room – making it part of a strategic policy keeps it in the board room.

Adopting an energy productivity target would put the UK at the forefront of energy policy. It would drive growth in the economy and innovation in policy and programmes, it would really start to address our mounting energy problems, and it would greatly contribute to the Chancellor’s goals of increasing resilence and creating sustainable growth.

Wednesday 9 November 2016

As a life-long Americaphile I can’t let the election of Donald Trump as President of the USA go by without comment. Before I do that it is worth explaining that my affection for America came originally from following the space programme, (landing a man on the moon was America at its best), but soon grew into something much wider. The bottom line is that America was founded on some great principles and ideals, admittedly principles and ideals that are often not lived up to, but nevertheless they are important and have had global significance. They were formed in the 18th century by giants like Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and James Madison. These men were people of their age and need to be viewed as such, but that was an age that welcomed rationality and knowledge – the Age of Enlightenment – a world we now seem to be rapidly moving away from. I have long followed American politics with all its craziness closely, I stayed up to the early hours of the morning to watch Nixon’s resignation speech in August 1974 – I don’t think many British 15 year old school boys did that. I have always argued that whatever dimension you look at, people, culture, technology, science, geography, whatever you want, America has the best and the worst in the world, and everything in-between. It is the land of extremes. The US often gets criticized because of the worst end of the spectrum. Unfortunately we now seem to be entering an era when some of the worst elements have the upper hand.

So what is going on in the US (and I am afraid in many other countries)? There is clearly anger and backlash at the mainstream politicians for not addressing problems that worry many people. Globalisation has brought enormous benefits but the problems of adjustment to de-industrialisation have not been properly addressed. Over the last ten to twenty years most of the increase in wealth has been concentrated in the hands of a few, whereas from WW2 on until the 1980s most of it benefited the working and middle class. Immigration, or rather mass migration, has caused and will continue to cause massive social, ethical and practical problems in the US and Europe. The perception (real or not) that immigration is uncontrolled is a huge issue and leads to xenophobia which can be exploited.

“Making America Great Again” is code for all these things as well as extreme views harking back to some imagined past when America really was the top dog and there were no problems in America. (Dumbest quote of the campaign: “there was no racism in America before Obama”). The reality is that America is still great but the world has changed and like everywhere it has a number of significant problems on the home front and internationally. The likelihood of a Trump presidency really solving these problems is extremely unlikely – the very few policies promoted during the campaign show little understanding of the issues.

The scariest aspects of a Trump presidency, and current trends in general, include:

- The rise of fact free debate and belief in crazy conspiracy theories.

- The rise of being able to repeat a lie multiple times and have it become a “truth” – despite evidence to the contrary.

- The rise of not trusting experts – “I know more about ISIS than the generals”. Really – how can that be?

- The links to Russia and comments about NATO are really worrying. I hope we never see it happen but the Baltics are really at risk.

- The rise of a bullying and misogynistic culture – remember that culture in any organization comes from the top.

- The rise of the idea that business is an “I win – you lose” game.

- The idea that Mike Pence may become President.

Hillary Clinton was clearly not a good candidate. Given her well known long-standing ambition to be President you would have thought she would have been more careful over things like emails. Using a home server was a seriously bad decision even though the actual security implications were probably very small. It shows a high degree of arrogance. It was interesting that we never got to see RNC emails or Trump’s tax returns – and now probably we never will. We will see what comes out of the Trump University case and other actions. The reality of a woman President will have to wait – probably for a long time. President Obama has done a good job in most areas but I don’t agree with all of his foreign policy shifts. He took office in the middle of the worst financial crisis since the 1930s but somehow that has been forgotten. The healthcare reform, for all of its problems, was a great achievement and if (when) it is rolled back people may look back fondly on the benefits they had for a few years.

In a number of his science fiction books set in the 2050s or beyond Arthur C. Clarke referred back to a global “time of troubles” between the 2010s and the 2040s before a return to rationality and global prosperity and peace. It seems as if he may have been right.

The expression “You can always count on Americans to do the right thing – after they’ve tried everything else” is attributed to Winston Churchill, although as with many sayings there is doubt he actually said it. Anyway it seems as if we may have to wait a long time while they are trying everything else – and hope the consequences aren’t catastrophic.

Dr Steven Fawkes

Welcome to my blog on energy efficiency and energy efficiency financing. The first question people ask is why my blog is called 'only eleven percent' - the answer is here. I look forward to engaging with you!

Tag cloud

Black & Veatch Building technologies Caludie Haignere China Climate co-benefits David Cameron E.On EDF EDF Pulse awards Emissions Energy Energy Bill Energy Efficiency Energy Efficiency Mission energy security Environment Europe FERC Finance Fusion Government Henri Proglio innovation Innovation Gateway investment in energy Investor Confidence Project Investors Jevons paradox M&V Management net zero new technology NorthWestern Energy Stakeholders Nuclear Prime Minister RBS renewables Research survey Technology uk energy policy US USA Wind farmsMy latest entries

- Ethical AI: or ‘Open the Pod Bay Doors HAL’

- ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning’

- You ain’t seen nothing yet

- Are energy engineers fighting the last war?

- Book review: ‘Stellar’ by James Arbib and Tony Seba

- Oh no – not the barriers again

- Don’t assume ignorance, sloth, bias or stupidity