Tuesday 19 August 2014

In my book “Energy Efficiency” (http://goo.gl/qxV1PR) I quoted examples of energy efficiency technologies in different applications across buildings, industry, transport and IT but of course it was only possible to have a small selection in the book. I am always interested to find examples of energy efficiency in sectors or applications that that don’t get much attention. On my recent travels to the USA for the Investor Confidence Project (http://www.eeperformance.org) I read of two aviation related examples courtesy of the American Airline inflight magazine.

The first concerned the new $50 million flight simulators for the American Airlines 787 Dreamliner. Of course flight simulators in themselves reduce fuel use enormously by training pilots on the ground rather than in the air. However, the interesting thing about the new 787 simulator, made by CAE, is that it is all electric. Previous generations of simulator used hydraulics to provide the multi-axis movement that helps to make simulators so realistic. The net result is a 75% reduction in average power use from 48kW to 12kW and a 50% reduction in peak power from 144kW to 72kW – impressive(1). The reduction in peak power will also reduce the cost of supply infrastructure (a co-benefit) in a new facility. Although the replacement of a simulator will never be driven by energy costs, rather by the lifecycle of simulators and aircraft, when the change is made there is a significant reduction in energy use and peak power. The point of this example is that there is huge potential to improve energy efficiency in all of our buildings, equipment and systems – energy efficiency potential is everywhere – we just have to look for it and apply good engineering and product development skills to exploit that potential.

The other example from American Airlines concerns the use of iPads for flight planning. Airline pilots use aeronautical charts and manuals and used to carry 35 to 40 lbs of paper into the cockpit (hence the need for the boxy black flight bags that every pilot and wannbe pilot had/has to have). The paper has now been replaced by iPads loaded with charts and manuals as well as pre-flight information, weather and apps for things like cross wind takeoff limits. The 35 to 40 lbs of paper has been replaced by 1.5 lbs of tablet. American Airlines estimate that the reduction in weight will save $1.2 million a year in jet fuel – a small drop compared to their total fuel spend and probably hard to measure but every little bit helps. Taking a systems view there will also be savings in paper (and energy used to make the paper), fuel savings in ground transportation used to deliver the paperwork and other significant co-benefits – possibly including reduced pilot downtime due to injuries caused by lifting those flight bags!

On a larger scale in aviation one of the main benefits of the 787 Dreamliner itself is of course its fuel efficiency. It has recorded a measured, in-service, 21% reduction in fuel usage per passenger compared to a Boeing 767. The need for greater fuel efficiency is driving aircraft fleet replacement and the retirement of older aircraft including the venerable Boeing 747 which revolutionized long-haul air travel and made it more accessible to all. The iconic 747 will be sadly missed by many – me included – when it finally leaves service but the pressures to improve fuel efficiency in aviation are inexorable.

Monday 4 August 2014

The escalating tension around the Ukraine has once again highlighted UK energy security. With the EU dependent on Russia for one third of its gas there has been a lot of media attention on gas supplies. The UK has taken a rather superior attitude by pointing out that we don’t import Russian gas and although technically true this ignores the fact that the European gas system is integrated and any disruption to supplies further East is likely to affect the UK. However, more importantly the focus on gas means that an important UK energy security issue has been totally ignored until now – and that is the problem of the UK electricity system using Russian coal. For some time I have been pointing out that a significant proportion of UK electricity is generated by Russian coal and that we should be concerned about this. Now I am glad to read in the Times (1st August) that Greenpeace has issued a report highlighting this issue and referring to the UK propping up Russian “coaligarchs” (great title). I don’t often agree whole heartedly with Greenpeace but on this issue I do.

UK dependence on imported energy rose to 47% in 2013, up from 43% in 2012. Coal generated 36% of UK electricity and 41% of that coal came from Russia. That means 15% of our electricity is generated using Russian coal and we are shipping off £1 billion a year to the Russian coal companies.

Well done to Greenpeace for highlighting the issue.

Energy use per capita and per unit of GDP continues to decline, total energy use fell 14% between 2000 and 2012 while the economy grew 58%. The old linkage between energy use and the size of the economy is broken – but in order to improve energy security and not be dependent on Russia (and other countries) we need to massively scale up energy efficiency across all sectors of the economy. We know the potential is there, we have the technology, and we know that as well as improving energy security enhanced energy efficiency brings many co-benefits including improved productivity, job creation and environmental protection. Massively scaling up energy efficiency is the least cost, least regrets route forward irrespective of your preferences on energy supply options. As we head into the 2015 general election, improving energy efficiency should be the first item on the energy manifesto of all political parties.

Monday 21 July 2014

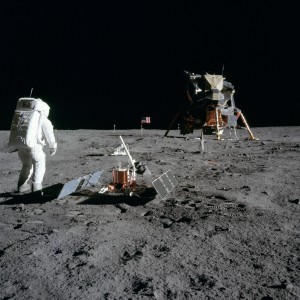

As many of my readers know my other interest in life other than energy matters is space – and specifically human exploration of space. I believe that exploration is hard wired into humans – otherwise we would still be living in the trees – and space exploration (and ultimately development) is the next logical step in our drive to explore. Of course we should also continue exploring Earth, especially the oceans – the loss of MH370 reminded us how little we know about the oceans – but we need to step up our presence in space.

Forty five years ago the Apollo 11 mission landed the first men on the moon. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin touched down on the Sea of Tranquility on 20th July 1969, carried out the first moon walk and then returned to their colleague Michael Collins orbiting the moon in the Command Module. They safely splashed down in the Pacific ocean on 24 July – thus fulfilling John F. Kennedy’s vision outlined in a speech to Congress on 25 May 1961: “this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth”.

I know that space exploration, and particularly now the emerging space tourism industry (which I believe will become a high-growth industry of the 2020s) can be controversial – especially amongst environmentalists but putting all that on one side, the 45th anniversary of Apollo 11 is a good time to remember just what an amazing achievement Apollo 11, and indeed the whole Apollo programme really was. It is also an excuse to remember some of the amazing facts about the Apollo technology – what NASA used to call “gee whiz data” because in the now archaic language of the 1960s it made you say “gee whiz”. I guess the modern equivalent would be “awesome” (although I am undoubtedly demonstrating that I am several generations of language behind in saying that).

The legacy of Apollo falls into several areas including technology, management and environmental consciousness.

Although the technology was (and still is) amazing the other incredible thing about Apollo was the management of such a complex, huge, high technology project. The programme employed 411,000 people at its peak (in 1965) and involved various government agencies as well as NASA, universities and the private sector. The management systems – mainly paper based in those days of course – worked well enough to bring all the people, resources, systems, components and money together and achieve the objective. In 1961 when President Kennedy set the objective (as clear and measurable an objective as there could be), many observers including many in the aerospace industry, considered that it was impossible. Even the methodology for going to the moon (Earth Orbit Rendezvous versus Lunar Orbit Rendezvous) was the subject of much debate and not finally settled until the middle of 1962. The Apollo programme truly demonstrates that humans can achieve anything we want to – if we have a clear objective and put the resources into it.

Another legacy from Apollo is its effect on the global environmental consciousness. There is little doubt that the photographs of Earth taken from the moon and enroute to the moon – particularly from Apollo 8 orbiting the moon in December 1968, gave us a new perspective on the Earth as a small, fragile “blue marble”.

American poet Archibald MacLeish wrote at the time: “To see the Earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the Earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold, brothers who know now that they are truly brothers.”

Many astronauts and cosmonauts since then have commented on the significant impact of seeing Earth from space, albeit “only” from Earth orbit as we have not revisited the moon since 1972. Sigmund Jaehn, the first German astronaut said:

“Before I flew, I was already aware of how small and vulnerable our planet is; but only when I saw it from space, in all its ineffable beauty and fragility, did I realize that humankind’s most urgent task is to cherish and preserve it for future generations.”

Anousheh Ansari, the first female private space explorer, fourth private space participant and first astronaut of Iranian descent who flew to the International Space Station in 2006 said:

“Nothing could have prepared me for the beauty of the view. It was breathtaking – watching the Earth from above without seeing borders, wars and divisions and realising how fragile the planet is. Every world leader should make the trip. They’d start to see things differently.”

The even greater impact of seeing Earth in its entirety from the distance of the moon – and being able to cover the entire Earth with your thumb – can only be imagined.

Although people talk about the technological “spin off” of Apollo and often incorrectly cite examples such as Teflon (actually discovered in 1938). Velcro (invented 1948) and the “space pen” (developed privately and not for NASA). There have been many real spin-offs from Apollo (and the Shuttle) but probably the greatest spin-off from the cold war space programme that culminated in Apollo was the huge increase in science and engineering education and expenditure that started after the first satellite Sputnik 1 shocked America. The generation of scientists and engineers that delivered Apollo, and the generation after that which was inspired by Apollo, built the foundations for the incredible technologies we use today.

Whatever your views on space exploration it is worth taking a minute or two to remember the enormity of the achievement of Apollo and the acknowledge the incredible, almost super-human, efforts of the more than 400,000 people that worked on the programme and the 29 astronauts who flew in Apollo – 24 of whom went to the moon and 12 of whom walked on the moon.

To finish up by returning to the theme of exploration, my favourite Apollo quote of all is not the well known “that’s one small step….” from Neil Armstrong but rather a quote from Apollo 15 Commander, David R. Scott, while surveying the landing site soon after touch-down on what was the most spectacular Apollo landing site at Hadley-Apennine:

“Man must explore and this is exploration at its greatest”

Some gee whiz facts about Apollo.

You often see a quote to the effect that a digital watch has more computing power than a Saturn V or some equivalent. The Lunar Module Computer and the Apollo Guidance Computer (identical machines – one in the Lunar Module and one in the Command Module) each weighed about 70 lbs, measured about 29” x 12” x 6” and had a power usage of 70 watts. The read-only memories were made of woven wire ropes with an equivalent of 72kb memory. For a brief over-view of the Apollo computer rope memories see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P12r8DKHsak.

The heat leak from the Apollo cryogenic tanks, which contain hydrogen and oxygen, was so small that if one hydrogen tank containing ice were placed in a room heated to 70 degrees F, more than 8 years would be required to melt the ice to water at just one degree above freezing. It would take approximately 4 years more for the water to reach room temperature.

When the Apollo spacecraft re-entered the atmosphere it generated energy equivalent to approximately 86,000 kWh of electricity – quoted at the time as “enough to light the city of Los Angeles for about 104 seconds; or the energy generated would lift all the people in the USA 10-3/4” off the ground”.

The Saturn V rocket itself was amazing. This was a vehicle weighing 2,700 tonnes – equivalent to a navy destroyer and 18 metres (60 feet) taller than the Statue of Liberty. The five F-1 engines of the first stage of the Saturn V produced 160,000,000 horsepower, “about double the amount of potential hydroelectric power that would be available at any given moment if all the moving waters of North America were channeled through turbines”.

The 12-foot-high Apollo Command Module contained about fifteen miles of wire.

For the best summary of the whole Apollo programme read Andrew Chaikin’s “A Man on the Moon”.

Normal energy related service will be resumed soon.

Thursday 3 July 2014

If anyone needed reminding this week about the risks around energy supply they only had to look at the satellite image below of Iraq’s largest oil refinery in flames. Recent events in Iraq as well as Ukraine have once again put energy security high on the agenda for governments and organizations.

Against this background The Crowd (http://www.thecrowd.me) held their Green Corporate Energy 2014 event on the 25th June and it was great to be a part of the team that launched a new initiative called the Energy Investment Curve.

The Energy Investment Curve

The Curve is an experiment in peer-to-peer sharing of data about energy investments made by corporates and public sector organizations. It is designed to allow people looking at energy investments to see what their peers are doing, learn from experience, help form business cases and provide a new source of data on what is happening in the market. Our vision is that it will help accelerate investment in energy demand side measures. It was designed to be easy to enter data as energy and sustainability managers are already deluged by numerous forms and data requests – the record for completing it with five investments was 14 minutes (subsequently broken after the event by a new contributor!). Anyone with an energy budget greater than £50k per annum can contribute their own data and once they do they can look at the overall results. The identity of contributing companies is protected. The data form is here: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/thecurve.

It asks for information on five energy investments covering; what it is, what was the capex, what is the payback period as well as general information about energy spend and payback thresholds. You can see an overview of the information we are collecting here. Once you have entered your information you will be able to access the results – you have to share to be able to benefit from the experience of The Crowd.

We think that the Energy Investment Curve will help you to:

- Find organizations that have made similar investments to ones you are considering – you can learn from their insights, and request an introduction.

- Compare your energy investment programme with others – both within your own sector and across sectors – helping you to see if you missed anything and where have others achieved different results.

- Support your investment cases, using the validation of others by seeing what their paybacks have been, and where they have found added benefits.

We had an initial 60 seed contributors who have provided data. A big thank you to them all – many leading organizations in energy and carbon management as well as the wider sustainability field. In summary the seed contributors had:

- an aggregate energy spend of more than £1 billion per annum (about 7% of the UK industrial and commercial energy spend)

- entered information on 160 investments

- a total investment of £360m

- an average payback period on that investment of 3.2 years

The Energy Investment Curve is designed so that the data can be looked at through three lenses:

- investment and payback

- co-benefits

- quality.

Investments and paybacks

Figure 1 shows the total investment by technology with payback period on the y-axis and the amount of investment in each category shown by the width of the column.

Even at this level the curve shows a number of interesting things including:

- the average payback period that is accepted for renewables (which includes CHP) at about 6 years is about twice as long as the average for all investments. Clearly organizations are accepting longer payback periods for renewables than for other investments.

- a large investment in power – this was skewed by a large investment in voltage optimization.

- behaviour change and software measures had quick payback periods which would be expected as they are both capital light measures

Figure 1. The Energy Investment Curve – all sectors – seed contributors

Wouldn’t you like to run through this list to check you haven’t missed possible investments? Well now, you can. And imagine if instead of 160 investments there were 1,600 rather than 160. The question to ask yourselves is “how long will it take you to identify all of these possibilities through the normal ways of doing business?” This is a tool for reducing the discovery time and it is a tool for sharing knowledge between organizations working to invest in energy demand side measures.

The curve allows you to search by sector so that you can see what your sector peers are doing. Figure 2 shows the curve for the retail sector.

There are 29 investments in the retail sector. Payback periods are slightly higher than the overall sample – 3.7 years versus 3.2 average. As you might expect the investments are dominated by power, refrigeration and lighting measures – which reflects the energy breakdown in the retail sector.

Figure 2. The Energy Investment Curve – retail sector – seed contributors

Using the Energy Investment Curve, energy professionals in organizations, suppliers and government can actually see the pattern of energy investment across different sectors – really for the first time. As well as helping organizations one of the problems for the energy demand side industry and government is simply measuring it – the Curve is a tool that enables measurement of the industry size and its breakdown between categories. This is important because we have always had trouble measuring the size of energy efficiency and demand side investment. If we take the sample as representative of the industrial and commercial sector as a whole (which may not be quite right due to the fact that the sample is large firms), we might estimate that the total investment in the energy demand side is of the order of £6 to £7 billion – which should be compared to the £12 billion that was invested in energy supply in the UK in 2013.

One of the problems in the whole energy arena is confusion of terms. A few years ago a group of us started using the phrase “D3” to encompass all demand side activities – D3 is Demand Management (permanent reduction of load – more commonly called energy efficiency), Demand Response (temporary shifting of load), and Distributed Generation (generation on the distribution system such as on-site renewables and CHP). The Energy Investment Curve showed that investment was split roughly 2/3rd to demand management (energy efficiency) and 1/3rd to distributed generation with only a small amount on demand response. Given the pressure on the electricity grid and the increasing number of schemes to encourage demand response the small investment in demand response was surprising – and perhaps worrying for the grid. It will be interesting to see how this changes over the coming years.

The investment in distributed generation was split as follows:

- Biomass (various forms) – £48m

- Photovoltaics – £47m

- CHP/trigeneration – £19m

- Wind – £5m

- Hydro – £1.8m

- Solar thermal – £30k

There were 13 investments in PV with a total investment of about £10m – ranging in size from £5,000 to £3.75 million.

Given the revolution in LED lighting that is happening it was not surprising to see the level of investment in LEDs. Of 25 lighting investments, 19 specifically mentioned LEDs and of the £49m invested in lighting, about £46m of this was in LEDs.

A quick and dirty calculation suggests that the energy investments produced a levelized cost of electricity of about £30/MWh and a levelized cost of £8/MWh for gas1 – supporting the contention that energy efficiency is the cheapest way of delivering energy services. Refinement of this calculation would be helpful for making the case that efficiency is cheaper than new supply.

Counting co-benefits

The second lens we can look at the Energy Investment Curve data through is co-benefits. The co-benefits of energy efficiency investments are really important and increasingly being recognized. The IEA is about to publish a big piece of work on co-benefits and some research shows that co-benefits of energy efficiency investments can actually be worth four times the energy savings, which would take a 4 year payback period project on energy alone to a 1 year payback period if those benefits are properly quantified and evaluated. That is only counting the benefits to the host – not including wider social benefits. Examples of co-benefits include better quality, removing production bottlenecks and increasing employee engagement.

A lot of the smarter energy management programmes are incorporating added benefits into their business cases. Tim Brooks of Lego (my all time favourite toy and inspirer of engineers everywhere) talked about this in his excellent presentation at GCE14. I can’t resist saying that Lego build up their investment case block by block incorporating co-benefits where they can. The uncertainty of some co-benefits is recognized in the process.

Other organizations are just recognizing the existence of benefits in their business case. For many years I have argued that energy and energy efficiency is a strategic matter – a matter of competitive advantage – and not just about cost savings. Catherine Cooremans, a business academic in Switzerland, has written extensively about the need to recognize the strategic value of energy efficiency investments (source 1 and source 2. Competitive advantage has three dimensions – COST, VALUE and RISK. Energy efficiency addresses all these three but my contention is that the energy efficiency industry has not been good at making this case – it has always focused on energy costs alone. We need to stress the existence of co-benefits and always include them in business cases. A rejoinder to this is that they are hard to measure – and that can be true – but business cases for other things like increased advertising are also often based on hard to measure variables. Co-benefits need to be valued wherever possible but at least recognized.

The Energy Savings Opportunities Scheme (ESOS) is coming into force soon in the UK and will mandate large organizations to have an energy survey every four years to identify energy saving opportunities. A good feature of ESOS introduced by DECC is that the survey has to be signed off by a board director. One of my concerns, however, is that energy surveys are done by energy efficiency specialists – who have also written the standards for doing energy audits such as EN16247. Standards for things like energy audits are good but traditionally audits only look for energy benefits and that is now enshrined in a standard. Energy efficiency industry and energy managers need to raise their game – particularly around ESOS otherwise we are in danger of repeating history and producing energy audit reports that identify opportunities but sit on shelves – unused because they don’t recognize co-benefits and the strategic value of energy efficiency. Back in the 1980s and 1990s we had to teach energy managers about investment appraisal techniques like IRR and NPV – now we need to teach them to look for and value co-benefits. It is no good complaining that the board does not recognize the co- benefits if no one identifies and evaluates them.

We looked at 13 co-benefits in the Energy Investment Curve including the obvious reduction in carbon emissions through to brand enhancement, employee engagement and reduction in supply risk. Figure 3 shows the results from the seed contributors for co-benefits – the size of the dot reflects how many times the benefit was mentioned. The most often mentioned co-benefit – no big surprise – is reduced carbon emissions. The second biggest is employee engagement, particularly in renewables and lighting, which are perhaps the most visible energy investments.

Interestingly renewables produced the largest employee engagement benefit as well as the largest carbon emission reduction benefit. Presumably this is to do with the very visible nature of many renewable investments such as PV and the ability to show data on energy production.

An example of co-benefits is given by the following example. A £1.75m resource conservation programme was rolled out across the west European sites of a Manufacturing / Industrial company. It paid back in around 18 months, and the company described it as “an excellent opportunity to engage with employees about what they can do to reduce energy & water usage” and gave it 5 stars.

Figure 3. Co-benefits – seed contributors

Investment star ratings

The third lens that you can use to look at the data from the Curve is star ratings of investments. Generally ratings were high but of course that can be expected as people are more likely to submit their good investments – the ones that went well – rather than the ones that went badly. Renewables had the widest range of star ratings – all the way from 1 to 5. This may reflect the fact that the renewables boom has attracted many new entrants, not all of whom may be high quality organizations, or perhaps more charitably it reflects the fact that this is a new area in which we are all learning. Figure 4 shows the ratings in the seed contributors’ data.

In the data you’ll find a 3rd party financed PV array by a retailer with a comment: “The third party funded nature of the array limits financial gain to our organisation but provides a visible carbon reduction and energy efficiency story to our customers, team members and stakeholders.” if you’re thinking about making a similar investment, you’ll be reassured by the comment and note the co-benefits but you’ll wonder why they only gave it a 3 star rating. If you do then you can use the Curve to request an introduction and find out more.

Figure 4. Star ratings – seed contributors

Problems with the data and improvements

The Energy Investment Curve we launched at Green Corporate Energy 2014 was a prototype – an experiment in co-creation – and can undoubtedly be improved. Amongst other things we have identified the following issues:

- We only asked for up to five investments – many organizations have made many more than five investments.

- We didn’t ask about the timescale over which the investments were made.

- People are likely to self select their best investments.

- There were some issues with categorization of investments.

- We should have allowed a free field entry for energy spend.

- We are relying on judgement rather than precise measurement but that is the philosophy of The Crowd.

- There was no question comparing actual to projected performance of the investments – although it appears that many organizations do not actually measure post-investment performance.

In the spirit of The Crowd we want to improve the Energy Investment Curve and expand its reach collaboratively. We are looking to form a small group to help improve it and steer its direction. We also want to expand its reach across the UK – and ultimately beyond – and will keep it open to new data. Please encourage other energy users to complete the data form.

Discussion

We know that there is still a massive opportunity for profitable investment in the energy demand side (D3) – in demand management (energy efficiency), demand response and of course distributed generation. Increasing the level of investment in these areas would bring great benefits to organizations – financial and other benefits – as well as to the country as a whole and the environment. D3 is the cheapest, cleanest and fastest energy resource that we have but it is not often thought about as a resource which sits alongside oil, gas, coal, renewables and nuclear. Many leading organizations over many years have shown that the energy efficiency resource just keeps giving. Companies like Dow Chemicals and 3M have consistently improved their energy efficiency and reduced consumption year after year and indeed decade after decade. Here in the UK BT has reduced its energy use year on year for five years, knocking £131m off its annual energy spend and reduced carbon emission by over 80% compared to 1996 baseline.

We hope that the Energy Investment Curve will grow and be used by many other organizations, helping them to increase investment in energy demand side measures and improve the returns from that investment, both from energy savings and the very valuable co-benefits. If we can do that we will be contributing to greater use of the demand side resource and helping to address the energy related problems we face – corporately, nationally and globally.

Steven Fawkes

28 June 2014

Wednesday 18 June 2014

I just finished reading “Edison Inventing the Century” by Neil Baldwin, an excellent biography of one of the most prolific inventors and entrepreneurs ever – one who still shapes our lives today. Edison’s most important innovation was not the light bulb, the phonograph (the one he was proudest of), the electric voting machine, the moving picture camera, the iron ore separator, the electricity meter, or the electrical distribution system, but the “invention of invention” – meaning the invention of systematic research and development to find solutions to technical problems and then improve upon them.

I have written before of the hype cycle in innovation and there is no doubt that Edison was also a master of hype – often announcing inventions were ready well before they actually were. He did, however, end up with 1,093 US patents (2,332 world-wide) – a number not surpassed by anyone until 2003 – making him one of the most prolific inventors ever. Another interesting part of the book covers Edison’s development of batteries for electric cars – a story with lots of resonance today.

Already by 1896 people were worrying about pollution from gasoline engine cars. Pedro Salom, a chemist, wrote in the Journal of the Franklin Institute; “all the gasoline motors which we have seen, belch forth from their exhaust pipe a continuous stream of partially unconsumed hydrocarbons in the form of a thick smoke with a highly noxious odour”. Obviously the control of combustion and fuel quality was not what it is today – and as well as pollution people worried about frightening the horses. Salom was not without a vested interest here as he co-founded the Electric Carriage and Wagon Company Inc. at the start of 1896. By 1900 Edison had decided electric cars were the way forward – they were outselling steam cars and gasoline cars at the time – and wanted to replace the heavy lead acid battery. He spent three years testing different alkaline batteries looking for longer life, durability, safety and a much better weight to energy ratio – all those parameters we continue to seek in battery technology today. He settled on using a positive pole of iron and a negative pole of superoxide of nickel with an aqueous solution of potassium hydroxide as an electrolyte – what we call a nickel-iron battery. He crash tested them by having them thrown from a third floor balcony – a great image.

In May 1901 Harper’s Magazine said: “the famous inventor considers his new storage battery the most valuable of all his inventions, and believes it will revolutionise the whole system of transportation“. He built an assembly plant which opened in May 1901 to produce “500 cells daily” with a target cost of $10 and sales price of $15. The plant produced different designs optimised for different vehicles including cars and delivery wagons plus illuminating train carriages. Edison’s fame and ability to get publicity led to a good start with strong sales for a year or so before technical issues were discovered. Cells leaked and power losses of 30 per cent occurred under repeated charging and discharging. Edison continued to innovate – adding nickel flake within the positive plate increased watt hour capacity per pound by 40 per cent – but in the end the market rejected electric vehicles as the gasoline engine improved and the problems with batteries were recognised. The business – The Edison Storage Battery Company – carried on making batteries for other applications and was sold to Exide in 1972 who then stopped making nickel-iron batteries in 1975.

Interestingly a 2012 Nature Communications article reported that Stanford University researchers had applied nano-technology to the nickel-iron battery with promising lab results – so perh

aps Edison’s technology will make a comeback.

Edison’s friend and collaborator on electric cars, Henry Ford once famously said “history is more or less bunk” but history can be helpful for understanding the present. “Edison Inventing the Century” has plenty of insight into the development of the modern electricity system as well as the (timeless?) issues around innovation.

Dr Steven Fawkes

Welcome to my blog on energy efficiency and energy efficiency financing. The first question people ask is why my blog is called 'only eleven percent' - the answer is here. I look forward to engaging with you!

Tag cloud

Black & Veatch Building technologies Caludie Haignere China Climate co-benefits David Cameron E.On EDF EDF Pulse awards Emissions Energy Energy Bill Energy Efficiency Energy Efficiency Mission energy security Environment Europe FERC Finance Fusion Government Henri Proglio innovation Innovation Gateway investment in energy Investor Confidence Project Investors Jevons paradox M&V Management net zero new technology NorthWestern Energy Stakeholders Nuclear Prime Minister RBS renewables Research survey Technology uk energy policy US USA Wind farmsMy latest entries

- The corruption of purpose in business – and how to address it

- Gee, I wish we could have a white Christmas, just like the old days….

- A look back at the last forty years of the energy transition and a look forward to the next forty years

- Domains of Power

- Ethical AI: or ‘Open the Pod Bay Doors HAL’

- ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning’

- You ain’t seen nothing yet