Tuesday 16 July 2019

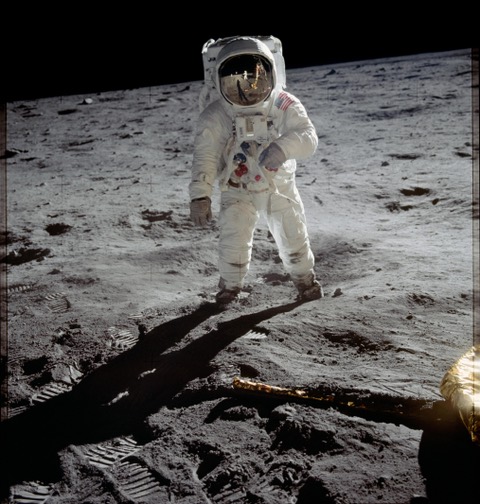

Even for those with no interest in space exploration it must be hard to avoid the fact that this month is the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 making the first landing on the moon. As regular readers know I have a strong interest in space and particularly the Apollo programme and so as in previous years I have to mark the anniversary in some small way.

Whichever way you look at it Apollo 11 – and the entire Apollo programme – was an incredible achievement, the result of eight years of dedicated, focused effort from up to 400,000 people, marshalled and directed by a government agency co-ordinating hundreds of contractors and sub-contractors. What can we learn from Apollo half a century on?

First of all there is the importance of a clear objective. President John F. Kennedy set out the objective in his speech to Congress on 25th May 1961, at which point the US had the grand total of 15 minutes of crewed sub-orbital space flight experience: “First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” This crystal clear objective came to be shortened as “man, moon, decade” and served as the touchstone for the programme and of course was achieved on 24th July 1969 when Apollo 11 splashed down in the Pacific and Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins were safely recovered onto the aircraft carrier USS Hornet.

Another lesson is the value of leadership taking bold steps. Throughout the Apollo programme political and programme leaders, exhibited boldness of a level which seems near impossible today. Douglas Brinkley in “American Moonshot” describes John F. Kennedy’s philosophy of courage as being “life is short, bold steps forward are immortal, so act.” The whole idea of landing on the moon inside a decade was so bold, especially so early in the development of space technology, that even many NASA managers were shocked by the commitment. The technology did not exist, even the method of getting to the moon (Lunar Orbital Rendezvous) was not decided until July 1962 – it was another three and half years before the ability to actually rendezvous in space at all was demonstrated by Gemini VI and VII. NASA’s decision to send Apollo 8 into lunar orbit in December 1968, driven partly by intelligence that the Soviet Union was planning a manned lunar flyby and by delays in the Lunar Module was incredibly bold. Apollo 8 was only the second manned Apollo flight and only the third launch of the monstrous Saturn V. The idea of sending Apollo 8 to the moon started in August 1968 with a final decision in November, after Apollo 7 had met its objectives in Earth orbit. In the four months before the mission the flight plan had to be developed, software written and the crew and Mission Control trained for a new mission.

Another lesson from Apollo is that exploration is hardwired into human DNA. Although the timing of the Apollo programme was driven by Cold War rivalries the idea of going to the moon and beyond is a centuries old dream. The advances in technology, many of which we are benefitting from today, and the scientific harvest were immensely valuable, but we explore because it is in our nature. Otherwise we would still be living in trees, or the ocean. Although we clearly need to address problems on earth we cannot suppress the desire to explore the solar system and beyond.

The power of purpose in organisations is now beginning to be recognised. Apollo – and space exploration – gave many people a higher purpose, one for which they were prepared to make great personal sacrifices. Admittedly there was no idea of life-work balance back then and many individuals and families paid a very high price but it was a choice made for a higher purpose. Some people of course, including astronauts and workers gave their lives.

In summary we can learn a lot from Apollo. We certainly need clear objectives to solve our environmental and social problems and we need bold leadership, something that appears lacking today – at least amongst politicians. Of course we also need the long-term financial commitments that underpinned Apollo – as JFK said in a less well known part of his speech to Congress, “I am asking the Congress and the country to accept a firm commitment to a new course of action, a course which will last many years and carry very heavy costs”. Yes, the programme was expensive, although tiny compared to defence spending, but its yield in terms of new technology, science, STEM education and the inspiration of generations of scientists and engineers was huge and continues to this day.

Having studied every detail of the Apollo programme I could find for more than fifty years I still find it incredible and the more I learn the more amazing it is. Even if you are not that interested in space I highly recommend reading at least one of the books or seeing at least one of the films commemorating the Apollo 11 anniversary. I recommend; “American Moonshot” by Douglas Brinkley, “Apollo 11 The Inside Story” by David Whitehouse and “Chasing the Moon” by Robert Stone and Alan Andres, which is also a documentary shown on PBS and the BBC. If you only do one thing see “Apollo 11” which tells the whole story of Apollo 11 in archive footage and includes some previous unseen 70mm film that was locked away for years and forgotten. Watch it and be amazed.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Dr Steven Fawkes

Welcome to my blog on energy efficiency and energy efficiency financing. The first question people ask is why my blog is called 'only eleven percent' - the answer is here. I look forward to engaging with you!

Email notifications

Receive an email every time something new is posted on the blog

Tag cloud

Black & Veatch Building technologies Caludie Haignere China Climate co-benefits David Cameron E.On EDF EDF Pulse awards Emissions Energy Energy Bill Energy Efficiency Energy Efficiency Mission energy security Environment Europe FERC Finance Fusion Government Henri Proglio innovation Innovation Gateway investment in energy Investor Confidence Project Investors Jevons paradox M&V Management net zero new technology NorthWestern Energy Stakeholders Nuclear Prime Minister RBS renewables Research survey Technology uk energy policy US USA Wind farmsMy latest entries